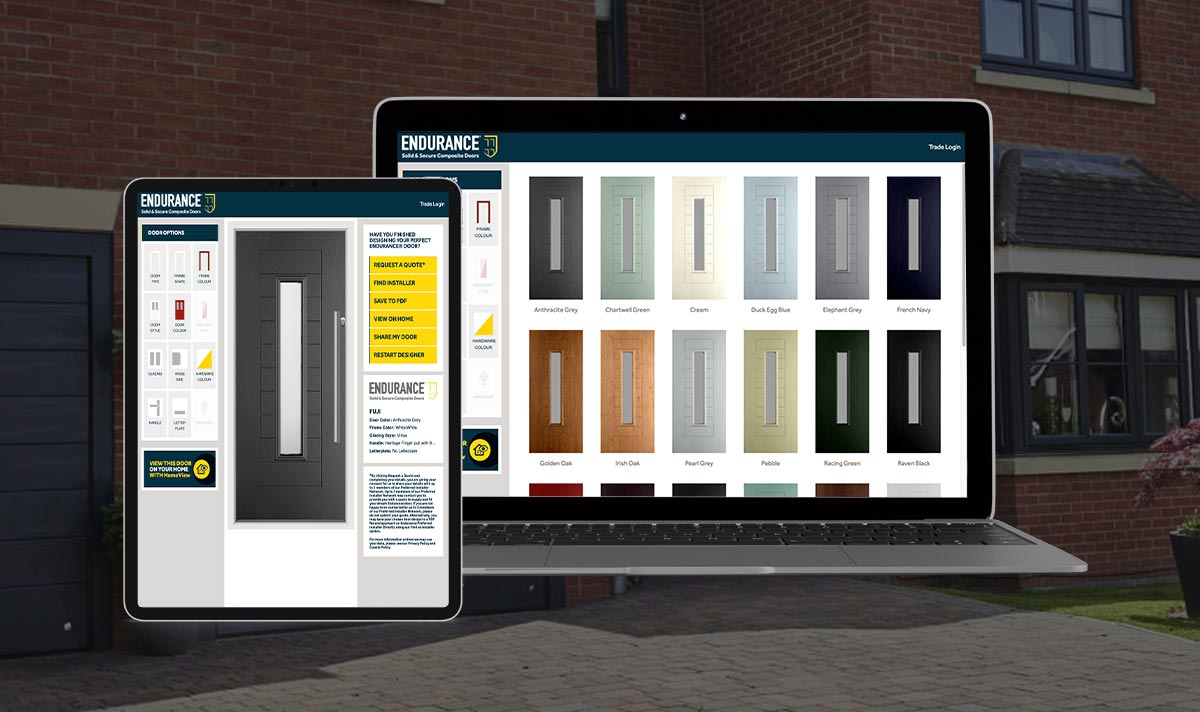

From Average Programmer to Industry Disruptor: The Story of How One Software Developer Revolutionized Window and Door Design

In the world of technology, stories of success often revolve around breakthroughs in social media platforms, […]

Top In-Demand Skills: SQL, Python, and Java

In today’s rapidly evolving job market, programming skills have become essential across various industries. According to […]

How I Became a Python Programmer—and Fell Out of Love With the Machine

In reality, the term “bare metal” is metaphorical. What lies beneath is silicon—thin layers of silicon […]

Apple Revises App Store Developer Policies Amid EU Investigation

Apple has updated its App Store policies in response to an EU investigation regarding its adherence […]

Java Virtual Threads: Case Study

Introduction to Java Virtual Threads The release of JDK 21 introduced Java Virtual Threads, a feature […]

Core Python Developer Suspended for Three Months

The Python Steering Council recently made a significant decision to suspend a core Python developer for […]

Microsoft Pushes .NET 9 Preview 6 with a Range of Improvements

Microsoft has unveiled the sixth preview of its upcoming .NET 9, a significant release for the […]