Malleable code by using decorators

Author: Kasper B. Graversen

[Introduction] [All categories] [All articles] [Edit article  ]

]

Design

SOLID

Single Responsibility Principle

Design Pattern

Decorator

Wrapper

Cache

Using the decorator design pattern, we get an exquisite separation of concern, while at the same time make the code more malleable.

Please show your support by sharing and voting:

Table of Content

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The all-in-one-class implementation

- 3. Cache as a wrapper object

- 4. Improving the design with decorators

- 5. Performance

1. Introduction

Recently with the v2.2.x versions of Stateprinter, we replaced the use of reflection (The GetValue() of FieldInfo and MemberInfo) with run-time code generation. It was a delirious moment, to see the overall run-time reduced by as much as 50%-75%. However, the joy was short, as new performance tests revealed crippling speeds for certain use scenarios. When instantiating a Stateprinter each time an object needed printing, insurmountable time was spent on run-time code-generation. Since there are very few types in a running program compared to the number of objects that may be printer, a cache holding the generated code, was an obvious choice.

To readers new to the Stateprinter paradigm, suffice to say, that Stateprinter is a simple framework for turning an object graph into a string representation. Such functionality can be used to generate ToString()-methods, for automating aspects of unit testing and updating existing unit tests, and finally work is currently in progress to greatly enhance the debugging experience. In other words, Stateprinter is envisaged to be a productivity booster. See more at https://github.com/kbilsted/StatePrinter

" The decorator pattern help separate concerns and make code more...

2. The all-in-one-class implementation

Let's look at the cache implementation as probably a lot of people would write it. Particularly when under pressure. In such times, focus is on getting things done rather than getting them perfect. Nothing wrong with that. But with the deadline behind us, a bit of self-reflection told us to revise the code. The code was conceived in a slight state of panic since the awful performance was discovered after a beta release of the code promising to the user, the aforementioned speed boost.

Fear not, if you have no experience with run-time code generation. Just think of it as a way to dynamically create a lambda or delegate for later invocation.

public class RunTimeCodeGenerator

{

static readonly Dictionary<MemberInfo, Func<object, object>> cache = new Dictionary<MemberInfo, Func<object, object>>();

public Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

// argument checking

if (!(memberInfo is FieldInfo) && !(memberInfo is PropertyInfo))

throw new ArgumentException("Parameter memberInfo must be of type FieldInfo or PropertyInfo.");

if (memberInfo.DeclaringType == null)

throw new ArgumentException("MemberInfo cannot be a global member.");

// cache look up

Func<object, object> getter;

lock (cache)

{

if (cache.TryGetValue(memberInfo, out getter))

return getter;

}

// run-time code generating

var p = Expression.Parameter(typeof(object), "p");

var castparam = Expression.Convert(p, memberInfo.DeclaringType);

var field = Expression.PropertyOrField(castparam, memberInfo.Name);

var castRes = Expression.Convert(field, typeof(object));

var generatedGetter = Expression.Lambda<Func<object, object>>(castRes, p).Compile();

// add or get value

lock (cache)

{

if (cache.TryGetValue(memberInfo, out getter))

return getter;

cache.Add(memberInfo, generatedGetter);

}

return generatedGetter;

}

}

You may frown at the use of Dictionary over say ConcurrentDictionary. That is a fair remark. However, since we try to stay compatible with .Net 3.5 we really didn't have a choice. In fact, for this article, it only makes the caching more convoluted, and hence better underlines the point I want to convey in the end.

The construction with locking twice is to reduce the time of each lock. This is important in situations where there is concurrency, say two request to a server. Recall, that lock is excluding all other access to the cache. By locking twice the total time we are locking the cache is reduced significantly, since we code generate outside a critical region.

From a readability and a malleability perspective this code is a bit of a mess. Parameter validation, cache lookups and run-time code generation all in one method. Blurred vision, purple haze. Not only that, but we are tightly coupling how we code generate with how we cache. We cannot easily use the same code generator with a different caching strategy, e.g. a LRU (Least Recently Used).

2.1 Extracting methods for clarity

In order to increase readability, let's extract the run-time code generation into a separate method. This separates functionality, and allows us to read and understand the code generation separately from the caching. We are not afraid of the extra method call this refactoring causes, it is easily in-lined by the JIT'er. Unfortunately, we are still tighly coupling the two concerns.

public class RunTimeCodeGenerator

{

...

public Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

if (!(memberInfo is FieldInfo) && !(memberInfo is PropertyInfo))

throw new ArgumentException("Parameter memberInfo must be of type FieldInfo or PropertyInfo.");

...

lock (cache)

{

if (cache.TryGetValue(memberInfo, out getter))

return getter;

}

var generatedGetter = GenerateGetter(memberInfo);

lock (cache)

{

if (cache.TryGetValue(memberInfo, out getter))

return getter;

cache.Add(memberInfo, generatedGetter);

}

...

}

Func<object, object> GenerateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

var p = Expression.Parameter(typeof(object), "p");

...

var getter = Expression.Lambda<Func<object, object>>(castRes, p).Compile();

return getter;

}

}

2.2 The need for further separation

Certainly, this makes the code clearer. But this technique only takes us so far. What we need is a better separation between caching and code generation. This proves advantageous for a number of reasons:

- We may re-use the code-generation code with a different caching strategy elsewhere in the code base.

- It is easier to test and understand two smaller classes rather than one big.

- It makes it easier to performance test when the cache is completely under control. Notice how the cached data is stored in a

static. Static is almost always evil. In our case, it makes it very difficult to performance test, the impact of a cold cache vs. a hot cache, since other test may have populated the cache. We could add functionality for clearing the cache, but for the current requirements that would only be needed for testing purposes. This is beginning to smell like a code smell... - The separation of an isolated cache class, making it an entity of its own, may enable you to think of caching in a bigger picture. Suddenly new ideas are born. You can envision different caching strategies, or maybe ways to binary externalize the state of the cache such that application reboot is not penalizing performance on the first few uses. A scholarly term for this is emergent behaviour.

3. Cache as a wrapper object

The first attempt at prying apart the two concerns, is by means of wrapping. We Create a cache-class which in turn calls the code generator. Users will always be using the cache class not the code generator.

public class RunTimeCodeGeneratorCache

{

static readonly Dictionary<MemberInfo, Func<object, object>> cache = new Dictionary<MemberInfo, Func<object, object>>();

static readonly RunTimeCodeGenerator generator = new RunTimeCodeGenerator();

public Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

Func<object, object> getter;

lock (cache)

{

if (cache.TryGetValue(memberInfo, out getter))

return getter;

}

var generatedGetter = generator.CreateGetter(memberInfo);

lock (cache)

{

if (cache.TryGetValue(memberInfo, out getter))

return getter;

cache.Add(memberInfo, generatedGetter);

}

return generatedGetter;

}

}

Notice how we are down a road of more elegant implementations. The class is solely focusing on getting the correct locks and returning cached values if any exist, or asking some one else for data to populate the cache.

Similarly trivial is the run-time code generating bit. Basically, it is the extracted method that has now found a new home in a separate class along with the parameter checking.

internal class RunTimeCodeGenerator

{

public Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

if (!(memberInfo is FieldInfo) && !(memberInfo is PropertyInfo))

throw new ArgumentException("Parameter memberInfo must be of type FieldInfo or PropertyInfo.");

...

var p = Expression.Parameter(typeof(object), "p");

...

var getter = Expression.Lambda<Func<object, object>>(castRes, p).Compile();

return getter;

}

}

To stress the point that the generator is being wrapped, it has been made internal. Alternatively, and to further stress the point of the wrapper, we could nested it inside of RunTimeCodeGeneratorCache and make it private.

The important thing here is that the users of the class will use references of type RunTimeCodeGeneratorCache. This has both a positive and negative impact. From a readability perspective, it becomes clearer that we are communicating with a cache and thus performance has been thought of by the author. But the very fact that the details of caching is pervading the code can be perceived to be a bad design. Certainly, the code is less malleable. The code using the cache cannot use a different cache or cache strategy without modification. From the perspective of dependency inversion (the D in SOLID), would instruct that the user code take any code generator, and IOC evangelists exclaim that the fact that we are using a cache around the generator should only be know at the composition root, which then is the go-to reference to understand the static structure of the code.

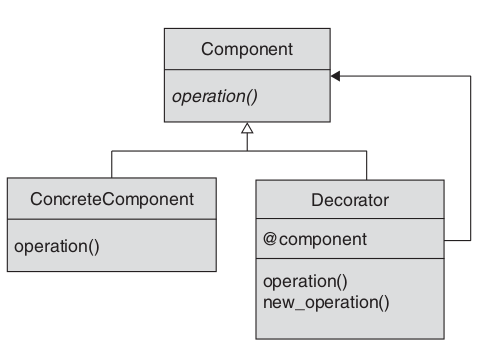

4. Improving the design with decorators

The decorator design pattern is similar to the wrapper object approach, but with the twist that both the wrapper and the wrappee share a common type, typically in the form of an interface. This enables multiple decorators to decorate the same object without changing any of the caller code. This allows us to apply multiple decorators without changing the caller code. As the code is split into smaller and independent units, we may find it easier to reuse the code. In other words, the code is more malleable.

The decorator design pattern is similar to the wrapper object approach, but with the twist that both the wrapper and the wrappee share a common type, typically in the form of an interface. This enables multiple decorators to decorate the same object without changing any of the caller code. This allows us to apply multiple decorators without changing the caller code. As the code is split into smaller and independent units, we may find it easier to reuse the code. In other words, the code is more malleable.

Usually malleability is an attribute of code that come for free when we strive to write code according to the Single responsibility principle (S in SOLID), Check out chapter 7 of Gary McLean Hall's book Adaptive Code via C#: Class and Interface Design, Design Patterns, and SOLID Principles for an indepth discussion and with rich examples on the use of decorators. If you prefer to read up on the SOLID principles from its origin, look at The Principles of OOD.

4.1 The decorator implementation

First we define a common type.

public interface IRunTimeCodeGenerator

{

Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo);

}

The cache is now slightly modified compared to the previous version. The decorator should not hard-code what it is wrapping, so a constructor takes a IRunTimeCodeGenerator as an argument. Potentially the code generator, but it could be another decorator. The implementation cares not - and shouldn't.

public class RunTimeCodeGeneratorCache : IRunTimeCodeGenerator

{

static readonly Dictionary<MemberInfo, Func<object, object>> cache = new Dictionary<MemberInfo, Func<object, object>>();

readonly IRunTimeCodeGenerator generator;

public RunTimeCodeGeneratorCache(IRunTimeCodeGenerator generator)

{

this.generator = generator;

}

public Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

...

}

}

Finally, the code generator, now made public and implementing IRunTimeCodeGenerator so we can pass it to the constructor of RunTimeCodeGeneratorCache.

public class RunTimeCodeGenerator : IRunTimeCodeGenerator

{

public Func<object, object> CreateGetter(MemberInfo memberInfo)

{

var p = Expression.Parameter(typeof(object), "p");

...

var getter = Expression.Lambda<Func<object, object>>(castRes, p).Compile();

return getter;

}

}

5. Performance

An interesting aspect of all this design mumbo-jumbo, is the potential speed penalties of the different strategies. Measurements are made using Stateprinter with 200.000 objects to print. Several measurements have been carried out in release mode and run-times averaged.

Before doing the measurements I was expecting the first, and ugliest, solution to be the better performer. Splitting code into classes potentially introduces method invocations (unless in-lined). But also using the interface type as the reference is commonly known also to incur significant overhead.

To my surprise there were bigger variation from execution to execution than between the three implementation strategies. For completeness here are the numbers:

| Strategy | Milliseconds | |

|---|---|---|

| One class | 3403 | |

| Wrapper | 3466 | |

| Decorator | 3409 |

Essentially, these figures are identical. But can we explain why this is the case. I have a few theories of mine

- We are implementing a cache mapping types to code generation. While we are processing many thousands of objects, they originate from the same class definition - thus the number of types exercised is countable on one hand. Our cache thus has a minimum of calls to the code generator

- Maybe since we are referring to the cached code generator from only one place in the code, which is a

readonlyvariable, the JIT'er is quick to discover that the interface type and the indirection it causes, can be optimized away.

Please show your support by sharing and voting:

Congratulations! You've come all the way to the bottom of the article! Please help me make this site better for everyone by commenting below. Or how about making editorial changes? Feel free to fix spelling mistakes, weird sentences, or correct what is plain wrong. All the material is on GitHub so don't be shy. Just go to Github, press the edit button and fire away.

Read the Introduction or browse the rest of the site